Macs aren’t known for their malware and viruses compared to, say, Windows PCs, but all operating systems have security vulnerabilities. macOS is essentially a Unix operating system with an Apple user interface, and that means it runs many common services and processes that hackers know how to exploit.

When it comes to security, a little knowledge is half the battle — specifically, knowledge of what’s taking place on your Mac behind all the pretty windows and icons. Antivirus software is fine, but a lot of malware doesn’t trigger antivirus programs, and targeted hacking certainly won’t. I use the Sophos Home antivirus product on my Mac at the moment, but it’s not helpful for telling me what it’s looking at and why, nor does it give me the ability to make decisions on what should be allowed and what shouldn’t. Besides, just as with personal physical safety, the best approach is a layered approach using multiple precautions in order to improve your chances of remaining secure.

Security is about what comes in, what goes out, and what modifies what. Most computers are always connected to the Internet and maintain a constant stream of incoming and outgoing connections. In addition, files on the computer are constantly being modified by running programs, whether those are part of the operating system or third-party applications. Finally, applications can also install new programs or services as a part of their operation. All of these happen constantly, with the computer user none the wiser. This is because there’s no user interface for these background processes.

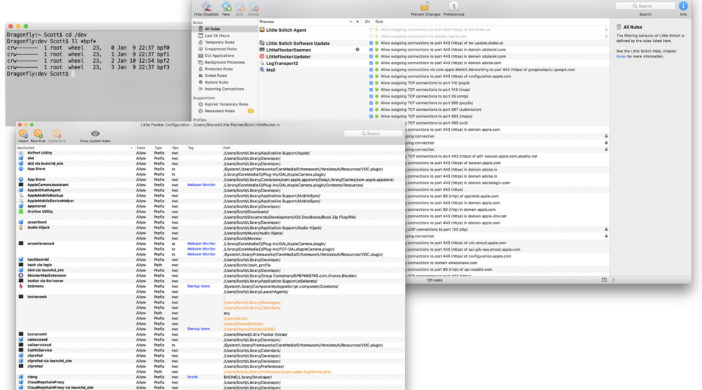

Well, that’s not completely true — you can always open a terminal window and use the Unix ps or top commands, or use Activity Monitor instead if you want a nice GUI. These will let you look at what processes are running on your Mac, but won’t tell you what started a given process or alert you to file changes and Internet connections. For that, you need something purpose built for the job. Fortunately, great Mac software abounds, and there are two applications in particular that I highly recommend, especially for curious and/or more technically-inclined Mac users: Little Snitch and Little Flocker.

Little Snitch

They say no one likes a snitch, but they couldn’t be more wrong when it comes to the first program on my short list, Little Snitch by Objective Development. Most people are familiar with the concept of a firewall, or have at least heard the term. It’s basically software that can reside on a computer or in a device like a Wi-Fi Router that attempts to keep out unwanted incoming network connections. Little Snitch is like that, except that it’s mainly for the purpose of monitoring outbound traffic rather than inbound traffic. It can and does have rules for inbound connections as well, however.

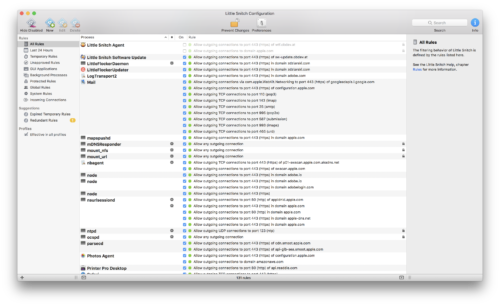

Little Snitch relies on two main concepts to do its job: alerts and rules. Rules are just what they sound like: rules that determine what outgoing (and incoming) network traffic is allowed as a matter of course without user intervention. Alerts are dialog boxes showing you detailed information when your Mac tries to connect to something on the internet or local network that you don’t already have rules set up for.

An example of a rule might be “For Adobe Creative Cloud, allow outgoing connections to port 443 (https) of domain adobe.ioâ€. This simply means that the Adobe Creative Cloud manager service running on my Mac is allowed to make connections to the domain Adobe.io over https.

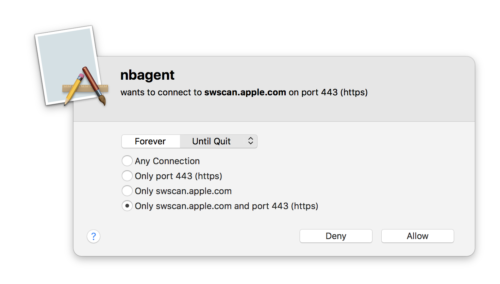

An example of an alert might be “nbagent wants to connect to swscan.apple.com on port 443 (https)â€. This means that some active process on the Mac called nbagent attempted an https connection to the domain swscan.apple.com, and Little Snitch not only wants you to know this, but also presents you with options for handling it.

Little Snitch allows tremendous flexibility in managing what the applications and processes running on your Mac can communicate to over the network and Internet. For example, using the nbagent example above, you can allow that to connect only to swscan.apple.com on port 443 as it is trying to do, or you can tell it it can connect to any server on port 443, or to swscan.apple.com on any port, or to any subdomain of apple.com on port 443, or any subdomain of apple.com on any port, or really to any server at all on any port it desires to. It’s that granular.

If this sounds like a major pain to manage, it kind of is – at first. Little Snitch is smart enough to come with a set of rules it thinks are necessary for your Mac to even be functional, and then you will go through an initial teaching phase where you have to decide what’s permanently allowed on your Mac. And make no mistake, the alerts can pop up at the most annoying times when you’re working on something or typing away, and you will curse Little Snitch under your breath at least one time. But once you get a week or so into it and have it dialed in, the pain will subside, your Mac will be safer, and you will be calmer and happier.

It’s because of this initial pain and because of the fact that you, the Mac owner, are required to disposition alerts to decide what is normal and allowable that I really recommend Little Snitch for more technically knowledgeable or curious Mac owners. If you look at the initial wave of alerts during the training phase and don’t understand what some of the processes on your Mac are, like nbagent or passwd, you’re going to be confused and possibly scared about what is happening on your Macintosh. Getting alerts and not having any clue what they’re talking about can seem alarming.

Interestingly, it’s for precisely this same reason that Little Snitch is a great learning tool. It will teach you both a lot about Unix and about Apple-specific services and online tools that the Mac uses on a regular basis. Google plus patience will reward you greatly if you approach Little Snitch as a security tool wrapped in a Computer 201 textbook. You probably have no idea that your Mac is running something called ocspd right now, or what it does, but you probably will if you use Little Snitch and start examining its rule set.

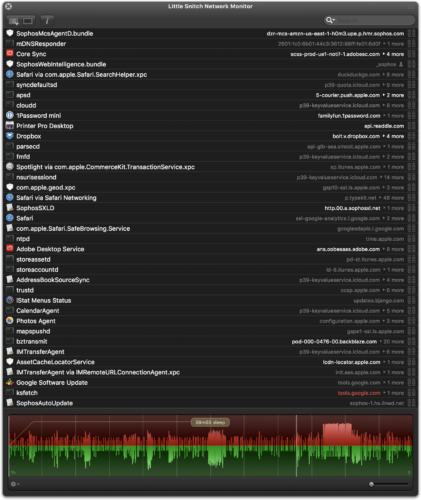

The bottom line is that your Mac should not be connecting to anything that you don’t want it to. Some of the things that it does connect to, but which you don’t know about, are in fact things you probably do want to let it connect to, but you’ll never know without a tool like Little Snitch. Several years have gone by between when I last used it and now, and I’m very glad that I installed it on my Mac again. It’s come a long way and is a valuable part of keeping a Mac safe and secure.

Little Flocker

The second piece of software that I want to recommend is one that I’ve come to know and love since its release in late 2016. It’s Little Flocker by Jonathan Zdziarski. Zdziarski is a computer forensics expert who knows a thing or two about security and who has a fascinating Twitter feed if you’re at all interested in the topic. He’s also pretty funny at times.

What Little Snitch does for network connections, Little Flocker does for the filesystem. If I recall correctly, the name of the program comes from a play on words related to the Unix flock utility, which is used to apply a type of lock on files. To simplify it somewhat, file locking is used to prevent multiple programs or processes from trying to change a file at the same time. Little Flocker, on the other hand, is used to keep files from being modified by rogue agents. The term rogue agents sounds really cool, but when it comes to your computer, it’s really not. You definitely don’t want people or malicious software to modify your precious files in ways you never intended or imagined.

I’ll give you two points if you can guess how Little Flocker does its job. Yes, you’ve guessed it – alerts and rules. And I have some news for you: files on your computer are being created, modified, and deleted all the time, and mostly not by you. So prepare for another burst of alerts after installing Little Flocker.

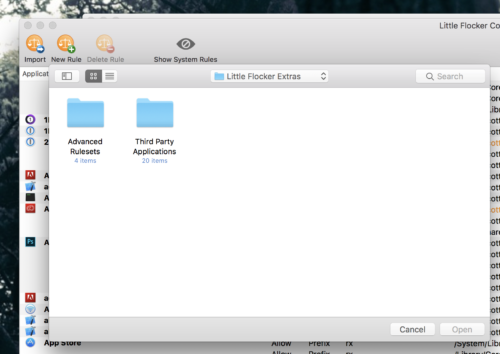

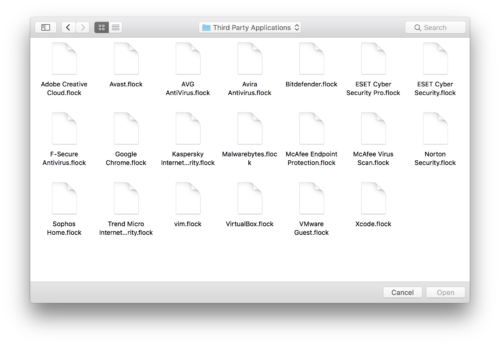

The good news is that, just like Little Snitch, Little Flocker has a base set of rules and they’re being added to all the time. Also, Jonathan Zdziarski has helpfully created .flock files you can import for specific things. For example, virus scanners constantly look at files and check network connections for bad things, so they need access in order to do so. Little Flocker has .flock files for several different virus scanner programs, including Sophos Home, which is what I use. Thanks to his foresight and Little Flocker’s ability to import rules and sets of rules, Little Flocker can instantly be taught how to allow applications to do their thing in the background. This is good, because without it, a virus scanner would blast you with enough incoming alarms to make NORAD’s alert system look like amateur hour.

There are also .flock files for things like Xcode, if you’re a Mac or iOS programmer, and Little Flocker can also do advanced things like NVRAM monitoring and allow control over kernel extension loading. You probably want to ignore those unless you really know what you’re doing. You can and should, however, allow it monitor your webcam and microphone, which it can also do. That’s a particularly useful thing given the prevalence of malware that likes to turn on cameras and microphones.

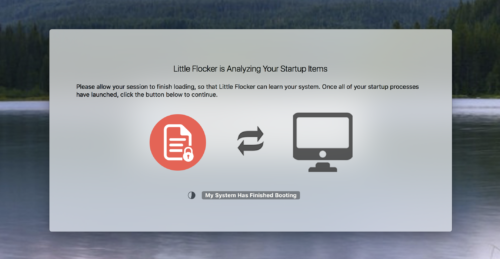

The best thing about Little Flocker in terms of avoiding more annoying alerts than necessary is its learning mode. When Little Flocker first starts up after installation or after an update to the program (both of which require a reboot of the Mac), it goes into learning mode. During this time, it watches to see what applications and services are loaded on your Mac during boot. This means that all of the stuff you have in your menu bar, as well as other services and programs you have running by default, will not throw red flags as far as Little Flocker is concerned. This helps a lot in getting Little Flocker’s rules set up and getting you past the annoying phase.

In addition, there is a Simple Mode option for people who can’t be bothered with the initial setup phase, or for those who are less confident about successfully decoding and correctly handling Little Flocker’s alerts. I haven’t used Simple Mode myself, so I can’t speak to how much of a difference there is between it and standard operation. According to Little Flocker’s website, it is simpler but also less powerful, meaning that using it results in reduced protection, which is to be expected if Simple Mode’s priority is minimizing user interaction.

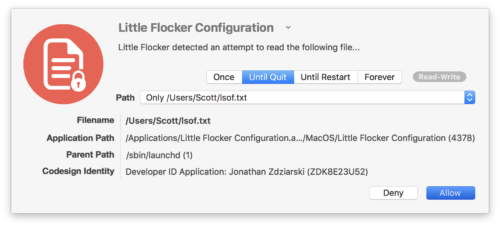

Like Little Snitch, approving a rule in Little Flocker gives you choices and granularity. For example, in the image below, I opened Little Flocker’s configuration window and Little Flocker itself is trying to access a file in my home directory.

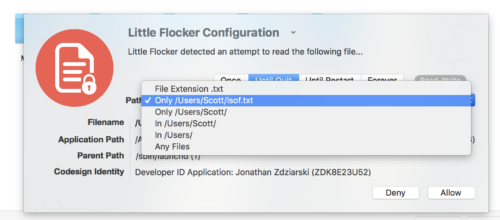

Little Flocker shows me what program is trying to access a file (in this case itself), what the file is, and what the file path is. I can choose to allow access one time, until the requesting program quits running, until the Mac is restarted, or forever. I can use the dropdown list showing the path to the file it wishes to access in order to allow the program to access anything from further up the path on down. In this way, I can give the requesting program access to all files in a specific folder or anything underneath a higher level folder. This negates having to create separate rules for a bunch of different PDFs in a Books folder, for example, or for all your videos under your Movies folder, even if they’re all in different subfolders.

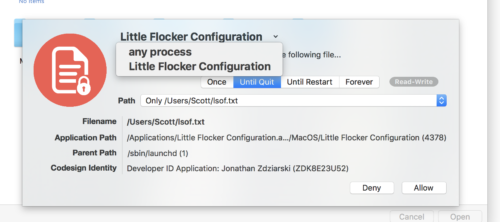

Finally, Little Flocker even allows me to choose whether to grant this access just to the requesting application (in this case Little Flocker) or to any process running on the Mac. That second option is nice to have, but it’s something you may want use sparingly lest you create routes of ingress for malware that you didn’t intend to.

You probably won’t be surprised to know that, as with the previously mentioned Little Snitch, Little Flocker is highly educational. It’s similarly best used by people who know at least a little bit about their Macs, or, once again, there may be more undue panicking at all the alerts that seem to make no sense. In fact, the alerts are well constructed and make it very clear what’s going on, but even for more advanced users there can be some confusion about why something is trying to access a specific file.

Here’s an example: macOS contains a utility known as bpf, which stands for Berkeley Packet Filter. Other programs can use it to inspect packets of information coming in from or going out to the network. One night, I got an alert that a Mac process known as mDNSResponderHelper wanted access to bpf. I know that mDNSResponderHelper is a normal Mac process, but I didn’t understand why it needed to use bpf. Generally, to the best of my admittedly limited knowledge, programs shouldn’t be doing a lot of raw packet inspection, and if there are programs that do, it’s probably because you installed them on purpose. I couldn’t think of anything I’d installed on purpose that would need to.

I thought maybe Little Flocker itself was trying to use mDNSResponderHelper to set up a bpf. mDNSResponder and mDNSResponderHelper are services related to how the Mac discovers other computers, devices, and services on a network. I sent Jonathan Zdziarski an email to his support email address and asked him if this might be the case. He replied that Little Flocker doesn’t use bpf for anything.

After further digging, I realized it was the Sophos Home antivirus program, which I had installed not long prior to getting the alert about mDNSResponderHelper and bpf. Considering that one of the functions of Sophos Home is to block malicious websites, this makes complete sense. It needs to be able to see what’s coming over the network in order to protect against it. My partial excuse for not realizing this is that I’d used Sophos Home in the past, and had just reinstalled it again after verifying that Sophos had fixed some Sierra compatibility issues with it, but I still felt pretty silly for not immediately understanding that it was the answer to my question.

The truth about mDNSResponderHelper and bpf turned out to be simple and completely benign. It is, however, illustrative of the fact that sometimes the things the Mac quietly gets up to in the name of helping make your life easier can be mysterious and confusing. Programs like Little Snitch and Little Flocker can illuminate those secret doings, but they can also confuse you and cause you worry if you don’t either already know something about how the Mac works or be patient and thorough with Google searches.

Little Flocker is a well written application with a nice Mac look and feel to it. It’s also a great program to have in the era of ransomware. Ransomware is malicious software that will encrypt your files, and then try to extort payment from you in exchange for the key to decrypt them again.

With Little Flocker, that type of malware will not have access to your files in the first place, because those programs are unknown and are trying to do things they haven’t been given permission to do (so long as you don’t create any crazily permissive rules under the any process category). In addition, you won’t need to worry that someone is looking at you over your webcam or listening to you on your mic without your knowledge. These are things that hackers really do nowadays, and you’d never know without something like Little Flocker to warn you.

Little Snitch and Little Flocker complement each other very well. Little Snitch has been around for years, while Little Flocker is basically a brand new product. I don’t know, but my guess is that maybe Jonathan Zdziarski came up with the idea for Little Flocker by looking Little Snitch and realizing how much need there was for something similar but for computer files instead of network connections. How right he was. These two programs together really form a solid one-two punch against sneaky invaders.

In my opinion, Little Flocker is a huge bargain. Little Flocker is priced at $14.99 for personal use on up to 5 computers. That should cover the average household nicely. At that price, if you’re even remotely interested, you don’t need to think about it. Just get it.

Little Snitch is slightly more expensive, but having been nudged back to it again by a conversation with my brother after several years of not using it, I’m glad I paid for it. It’s also worth buying, at $34.95 for one Mac or $69.00 for a family license.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.